[T]he best way to predict Obama’s foreign policy in the next three years lies not in examining how he deals with the accumulated baggage of Iraq, Afghanistan, Middle East peace, and the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs. Important as those are, they constitute what Obama has had to confront. We should ask instead what he will attempt to establish once he has become less encumbered by the inherited issues. Here, the record shows three critical characteristics.

[T]he best way to predict Obama’s foreign policy in the next three years lies not in examining how he deals with the accumulated baggage of Iraq, Afghanistan, Middle East peace, and the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs. Important as those are, they constitute what Obama has had to confront. We should ask instead what he will attempt to establish once he has become less encumbered by the inherited issues. Here, the record shows three critical characteristics.

First, Obama has no particular interest in foreign and national-security policy. That is not what he has spent his professional and political career, such as it is, doing, and it is not where his passions lie. There can be no question that the challenges of remaking America’s health-care, financial, and energy-production systems claim the bulk of Obama’s attention.

Second, Obama does not see the rest of the world as dangerous or threatening to America. He has made it clear by his actions as president that he does not want to engage in a “global war against terrorism.” The rising power of other nations, creeds, and ideologies, however unsavory, pose no grievous challenge to which the United States must rise. We are not at a Dean Acheson–style, post–World War II “present at the creation” moment. Therefore, Obama reasons, why behave in reactive, outmoded ways when there are many more interesting and pressing domestic projects to nurture?

Obama’s America need only be restrained, patient, and deferential. Take, for example, Obama’s November 2009 trip to China, during which the media highlighted how unyielding Beijing was, thus confirming their “rising China/declining America” conventional wisdom. In fact, it was more Obama’s submissiveness and less China’s assertiveness that made the difference on issue after issue: trade policy and Chinese currency manipulation; Taiwan; Beijing’s unwillingness to limit growth for the sake of global-warming theory; and Iranian and North Korean nuclear-weapons programs. Obama repeatedly came away empty-handed, even on blatantly cosmetic aspects of the visit: where he would speak, to whom, and how it would be broadcast.

Third, Obama’s vision is embedded in a carapace of naive internationalism, a very comfortable fit when national security is neither that interesting nor that important. Obama is the first president since December 7, 1941, to espouse a determinedly unassertive global role for the United States, one ironically verging on an essentially neo-isolationist view of America. Obama’s December 1 announcement of troop increases in Afghanistan is not to the contrary, since he proclaimed the beginning of withdrawal in virtually the same breath. Afghanistan, like Iraq, is the very paradigm of legacy issues Obama does not want to confront. Failures such as his Middle East peace process and dealing with Iran and North Korea have simply led to resignation and inattention.

However, Obama’s is not your grandfather’s isolationism. He focuses not on America’s virtues but on why it is ordinary (thus explaining why, as I have written elsewhere, he is firmly “post-American”). It is America’s ordinariness that should enjoin it from imposing its will upon other nations. Obama is our first sitting president to express this sentiment. In April, he articulated this point with absolute clarity. Asked if he believed in American exceptionalism, the president responded, “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.” In other words, “No.”

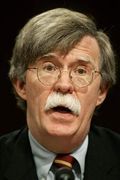

(John R. Bolton, "Obama's Next Three Years," Commentary 129 [January 2010]: 24-8, at 24-5 [footnote omitted])

Note from KBJ: Imagine how Michelle Obama would feel if, when her husband was asked whether he believes she is exceptional, he replied, "I believe that Michelle is exceptional, just as I suspect that every other husband believes his wife is exceptional." There is something evasive about this answer. The question was not (despite its formulation) whether he believes that Michelle is exceptional, but whether she is exceptional. Not all beliefs are true, after all. The Brits and Greeks may have false beliefs about their countries. This doesn't make Americans' beliefs false.

Note 2 from KBJ: The more I think about this, the more troubling it becomes. Why would President Obama talk about what other people believe when asked what he believes? He seems to be saying that no country could possibly be exceptional. "Yes, everyone, including me, believes that his or her country is exceptional, but there is no basis in reality for this." By this logic, there is no basis in reality for saying that Barack Obama is exceptional. Is this man a nihilist? He seems unable or unwilling to make value judgments.