Among such of the primitive modifications of the corporeal frame as may

Among such of the primitive modifications of the corporeal frame as may

appear to influence the quantum and bias of sensibility, the most

obvious and conspicuous are those which constitute the sex. In

point of quantity, the sensibility of the female sex appears in general

to be greater than that of the male. The health of the female is more

delicate than that of the male: in point of strength and hardiness of

body, in point of quantity and quality of knowledge, in point of

strength of intellectual powers, and firmness of mind, she is commonly

inferior: moral, religious, sympathetic, and antipathetic sensibility

are commonly stronger in her than in the male. The quality of her

knowledge, and the bent of her inclinations, are commonly in many

respects different. Her moral biases are also, in certain respects,

remarkably different: chastity, modesty, and delicacy, for instance, are

prized more than courage in a woman: courage, more than any of those

qualities, in a man. The religious biases in the two sexes are not apt

to be remarkably different; except that the female is rather more

inclined than the male to superstition; that is, to observances not

dictated by the principle of utility; a difference that may be pretty

well accounted for by some of the before-mentioned circumstances. Her

sympathetic biases are in many respects different: for her own offspring

all their lives long, and for children in general while young, her

affection is commonly stronger than that of the male. Her affections are

apt to be less enlarged: seldom expanding themselves so much as to take

in the welfare of her country in general, much less that of mankind, or

the whole sensitive creation: seldom embracing any extensive class or

division, even of her own countrymen, unless it be in virtue of her

sympathy for some particular individuals that belong to it. In general,

her antipathetic, as well as sympathetic biases, are apt to be less

conformable to the principle of utility than those of the male; owing

chiefly to some deficiency in point of knowledge, discernment, and

comprehension. Her habitual occupations of the amusing kind are apt to

be in many respects different from those of the male. With regard to her

connexions in the way of sympathy, there can be no difference. In point

of pecuniary circumstances, according to the customs of perhaps all

countries, she is in general less independent.

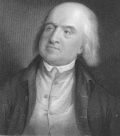

(Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, ed. J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart, in The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. F. Rosen and Philip Schofield [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996], chap. 6, sec. 35, pp. 64-5 [italics in original] [book first published in 1789])

Note from KBJ: I can't think of a single female utilitarian, past or present. Bentham explains why.