We cannot judge an action to be right for A and wrong for B, unless we can find in the natures or circumstances of the two some difference which we can regard as a reasonable ground for difference in their duties. If therefore I judge any action to be right for myself, I implicitly judge it to be right for any other person whose nature and circumstances do not differ from my own in some important respects. Now by making this latter judgment explicit, we may protect ourselves against the danger which besets the conscience, of being warped and perverted by strong desire, so that we too easily think that we ought to do what we very much wish to do. For if we ask ourselves whether we believe that any similar person in similar circumstances ought to perform the contemplated action, the question will often disperse the false appearance of rightness which our strong inclination has given to it. We see that we should not think it right for another, and therefore that it cannot be right for us. Indeed this test of the rightness of our volitions is so generally effective, that Kant seems to have held that all particular rules of duty can be deduced from the one fundamental rule "Act as if the maxim of thy action were to become by thy will a universal law of nature." But this appears to me an error analogous to that of supposing that Formal Logic supplies a complete criterion of truth. I should agree that a volition which does not stand this test is to be condemned; but I hold that a volition which does stand it may after all be wrong. For I conceive that all (or almost all) persons who act conscientiously could sincerely will the maxims on which they act to be universally adopted: while at the same time we continually find such persons in thoroughly conscientious disagreement as to what each ought to do in a given set of circumstances. Under these circumstances, to say that all such persons act rightly—in the objective sense—because their maxims all conform to Kant's fundamental rule, would obliterate altogether the distinction between subjective and objective rightness; it would amount to affirming that whatever any one thinks right is so, unless he is in error as to the facts of the case to which his judgment applies. But such an affirmation is in flagrant conflict with common sense; and would render the construction of a scientific code of morality futile: as the very object of such a code is to supply a standard for rectifying men's divergent opinions.

We cannot judge an action to be right for A and wrong for B, unless we can find in the natures or circumstances of the two some difference which we can regard as a reasonable ground for difference in their duties. If therefore I judge any action to be right for myself, I implicitly judge it to be right for any other person whose nature and circumstances do not differ from my own in some important respects. Now by making this latter judgment explicit, we may protect ourselves against the danger which besets the conscience, of being warped and perverted by strong desire, so that we too easily think that we ought to do what we very much wish to do. For if we ask ourselves whether we believe that any similar person in similar circumstances ought to perform the contemplated action, the question will often disperse the false appearance of rightness which our strong inclination has given to it. We see that we should not think it right for another, and therefore that it cannot be right for us. Indeed this test of the rightness of our volitions is so generally effective, that Kant seems to have held that all particular rules of duty can be deduced from the one fundamental rule "Act as if the maxim of thy action were to become by thy will a universal law of nature." But this appears to me an error analogous to that of supposing that Formal Logic supplies a complete criterion of truth. I should agree that a volition which does not stand this test is to be condemned; but I hold that a volition which does stand it may after all be wrong. For I conceive that all (or almost all) persons who act conscientiously could sincerely will the maxims on which they act to be universally adopted: while at the same time we continually find such persons in thoroughly conscientious disagreement as to what each ought to do in a given set of circumstances. Under these circumstances, to say that all such persons act rightly—in the objective sense—because their maxims all conform to Kant's fundamental rule, would obliterate altogether the distinction between subjective and objective rightness; it would amount to affirming that whatever any one thinks right is so, unless he is in error as to the facts of the case to which his judgment applies. But such an affirmation is in flagrant conflict with common sense; and would render the construction of a scientific code of morality futile: as the very object of such a code is to supply a standard for rectifying men's divergent opinions.

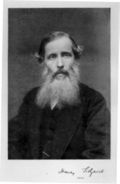

(Henry Sidgwick, The Methods of Ethics, 7th ed. [Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1981], bk. III, chap. I, sec. 3, pp. 209-10 [first published in 1907; 1st ed. published in 1874])

Note from KBJ: Sidgwick is saying that universalizability is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for rightness. An act can be shown to be wrong by showing that it is not universalizable; but it cannot be shown to be right by showing that it is universalizable.